Eco & the economics of communes

The focus of our eco-village is not to just be at one with nature but to be in concurrence with others. To not care about how you look, to take off the mask you wear every day to play this role in society.

Pseudo Research, Zegg Community, Germany

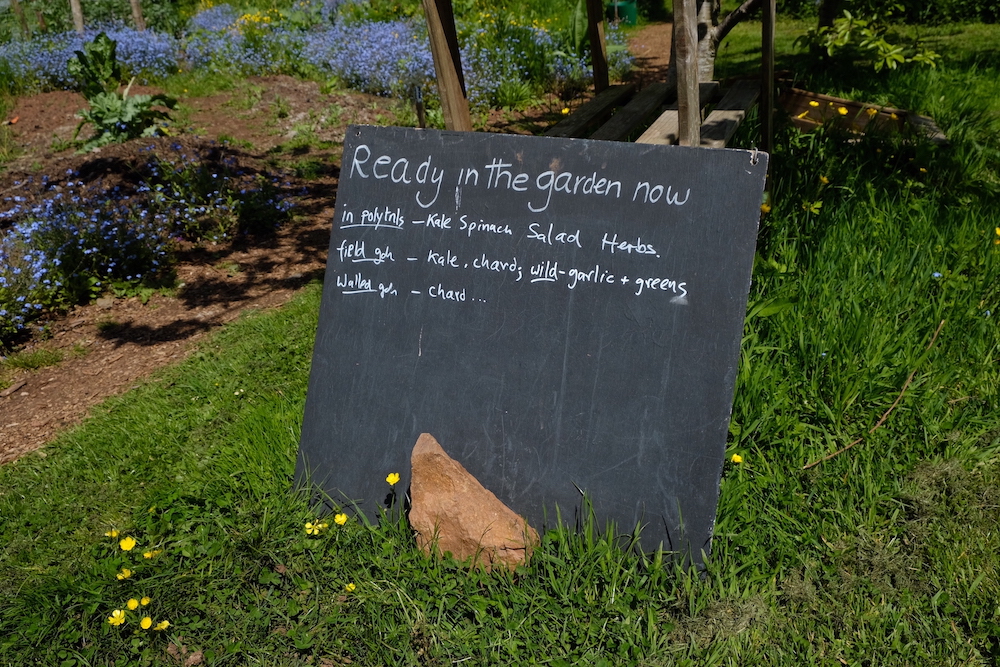

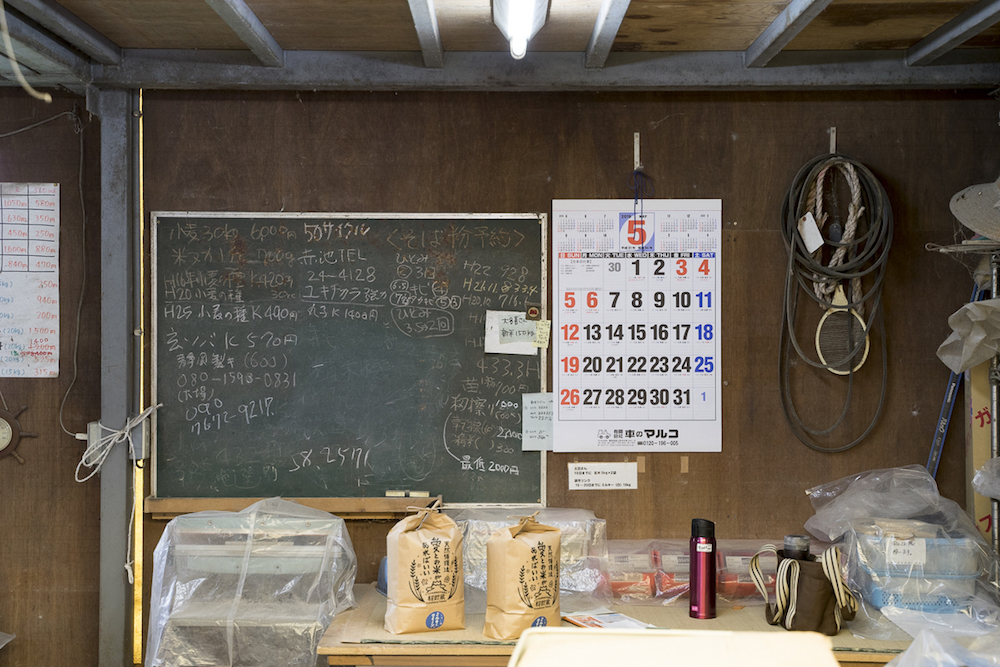

Over the years, we’ve researched various communes, from long-standing rather ‘traditional’ ones in England and America to more modern [typically student] ones in France and Germany, and to rather cult-like ones in Japan. During our time with the communities there, we’ve danced, we’ve wheelbarrowed, we’ve cooked, we’ve cleaned, we’ve canned, we’ve collected. Whatever they did in the communes, we did too. Observationally, it was a slower but equally busy way of life, with consideration consistently paid to the footprints that each commune left on the earth as well as their behaviour within it.

Largely considered a product of the hippy movement, communes are actually a lot older than that, with the 60s adopting the term rather than creating the actual idea of a commune. Derived from the Latin word ‘communia’, it means ‘common’ or ‘general’. In France, in 1872, it was cited as meaning ‘a community organised and self-governed for local interest, subordinate to the state.’ This idea of ‘self-interest’ still lies at the heart of most communes today - following the footsteps of the Pilgrims in the 1600s and the Shakers in the 1700s.

The 60s arguably swelled the idea of the self-interest space, attracting creative and counter-culture groups to their shared spaces by promising them the idea of ‘back-to-land living’. Going up against the establishment and leaning into the idea of a new freedom, the communes of the 60s could be seen in the likes of The Castle in Los Angeles, situated at the Haight-Ashbury intersection. Seen as ‘a symbolic marker for the start of the commune obsession’ [read more here], it attracted the likes of Andy Warhol, Nico, Lou Reed and even Bob Dylan [the latter of this list became a guest for quite some time there]. For many, communes were not about dropping out of society for society’s sake but rather, a hope that their very existence would shock the mainstream into departing from ways that didn’t work, inspiring people to do things differently.

Today, within the commune community, they rarely use the word, preferring instead to talk about cooperatives, eco-villages, intentional communities and shared living, thereby distancing themselves from the stereotypes that the Sixties intrinsically built into these communal spaces. [Indeed, for all the ‘communes’ we visited, they’d picked one of these words to describe themselves; one Japanese commune was an ‘eco-village’, one was a ‘shared living space’, another ‘an intentional community.’] Our times at these communes, whatever they decided to call themselves, were gentle, busy and considered, with everything layered with tolerance, patience and kindness - key foundations of a successful space.

Yet Vice journalist Rich Thorton’s year of visiting communes across the world was a slightly different experience to ours. Opening his article with the daydream of burning his Air Maxes and dancing with Druids before he got there, he found the communes to be “a bureaucratic Internet maze of credit card payments, application forms, and groups of middle-aged people making sure they washed at 30 degrees.” He noticed that “[Communes] are not hippy playgrounds for kids who hate their parents. They are serious endeavours by committed activists who want to experiment with sustainable ways for humans to live together and look after the planet. And in order to achieve this aim within our global capitalist society, they've had to open bank accounts.”

And in some ways, he’s right. For they are more structured than before, with the Suffolk Manor House even setting up their own government during Covid, yet, the ideas behind these shared spaces are still the same: ‘do good, do better, do it together.’

I've lived in various, different types of intentional communities where we've had various different types from an income sharing community to communities like this one where we don't. It is nice to have a very clear programme and understanding. It's nice to able to monetise things sometimes.

Pseudo Research, Emerald Earth Resident, California

But what’s the future of sharing space? By 2050, tracked trends expect that 70% of the world’s population will be urban-dwelling, creating even bigger problems for many governments regarding housing, jobs and the economy. And we know that high-density living has its problems, as most major cities [especially in the West] are also seeing - with soaring rents, stagnant and falling wages, and reduced housing stock. Increasingly, sharing space is likely to become more of a consideration, especially since bills and responsibilities can be shared [let alone child care, education, food, etc.]. And covid kicked part of this trend off, becoming a catalyst for people to seek out cooperative spaces, looking to feel more ‘a part of’ rather than ‘apart from’. Indeed, the multi-generation community Bergholt in Suffolk - one of the longest-standing farming communities in the UK - received 70 applications in just April and May of 2021 alone. Couple covid with the cost-of-living crisis, and the appeal only extends even further. Whether it’s the idea of living off-grid or simply sharing the cost of living by living together, the allure of the shared space - whatever you care to call it - is undoubtedly attracting new faces and new generations to this old way of life…

Being a part of the resilience movement here means that we can make real changes every day that will be making a positive impact. If we continue to think about the future we forget about the present. We need to be making steps every day to be a lower-impact society. Statistics and targets are good but spend too much time on that and you forget about what you can be doing right now in the present.

Pseudo Research, Lyon Commune, France

Photo Credit: Lily Noel / Fernanda Liberti