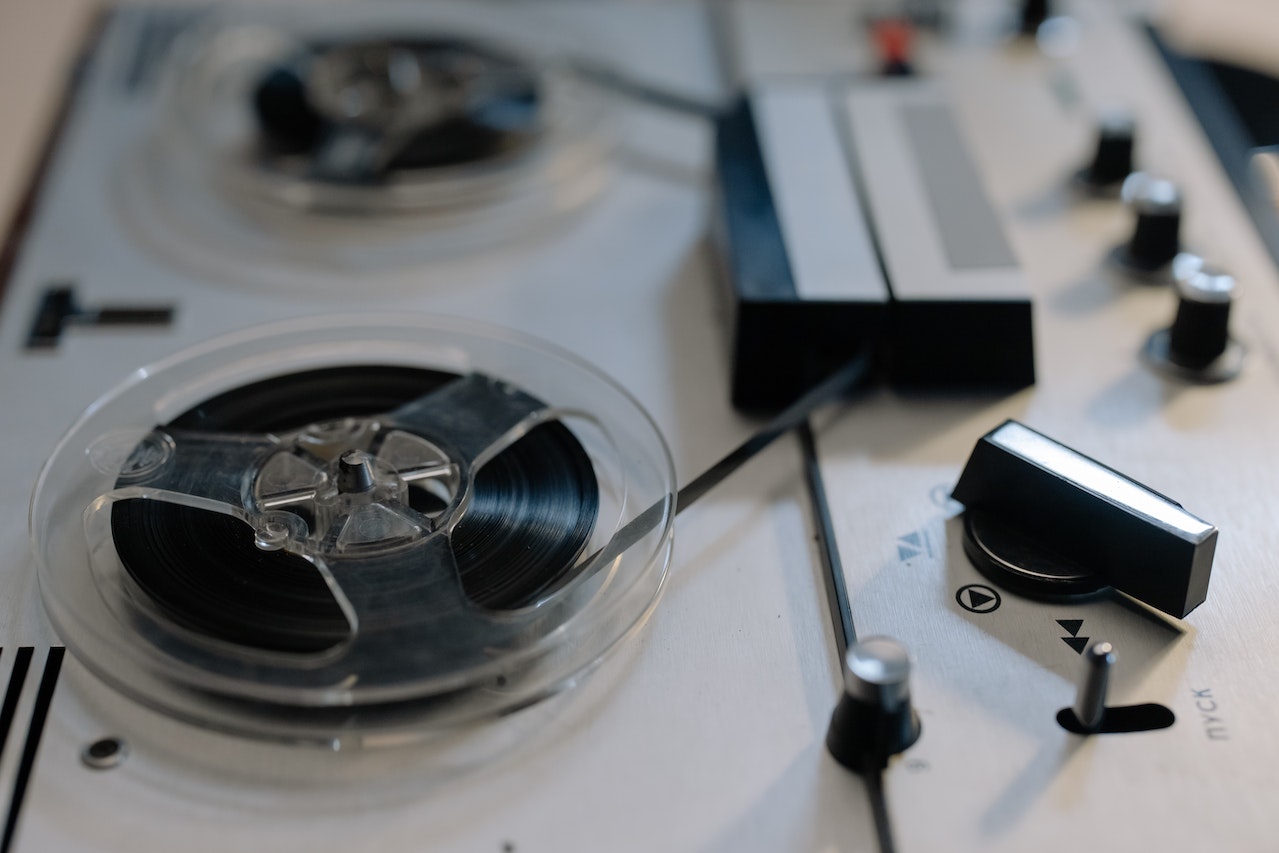

Part One | I is for Interrogator

People often ask me what I do, and sometimes I just shortcut to, “I collect interesting people for a living.” During the pandemic, I gave exactly this answer to a friend of mine, who then suggested I speak to a friend of his. Why? Because his friend was an ex-interrogator and liked to talk and my friend thought his friend would enjoy it.

And talk he did. For three hours. Over Zoom. While eating homemade soup.

My partner Terry—a great conversationalist—chatted with him, interrupted only by the arrival of said homemade soup that, for some reason, Terry thought was a cream bun—as if interrogators eat cream buns while talking…

The transcript, at 55 pages long, was typed by me; the following is an excerpt from that. Here we introduce the interrogator, who we name ‘Simon’ but is very much not called Simon, but is someone who eats soup.

Before we start, it's important to note that we spoke to Simon, not about who he interrogated, but more about his human interactions — how to empathise with people and how to relate and build rapport with those to whom you may have diametrically opposed ideals and values.

The Road To Interrogation:

Simon’s journey to become an interrogator wasn’t a streamlined, planned-out one. Carrying out numerous roles before he got there, he was a student, a teacher, a salesman, and a business owner. In fact, his journey didn’t start until the late 90s when he was in his forties, a time when he found himself working in Category A [and double A] prisons, housing “the sort of people that you usually find in places like that.” He found, by accident, that he had a way of getting the prisoners to talk to him, eventually "feeding stuff back to the powers that be”, essentially the anti-terrorist units housed within the prisons.

RP: So how were you able to get information from category A prisoners within the context of them knowing they were speaking to someone official? A guard as such.

Simon: You interrogate in this exact format: you treat everyone as a person. You don’t treat them as a terrorist or a murderer or a rapist or anything like that. You treat them as a person because 98% of their persona is normal, or rather, ‘communal’ if you like. We are all people, and 98% of our interests are pretty damn similar, you know? Food, living environment, family, all those sorts of things, and it’s just a very small percentage in which we differ.

RP: Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, essentially?

Simon: Exactly. So, I would come at people - and always have done - as individuals and as people. Establish that rapport, get that rapport going, and once you have that rapport and that trust, then stuff just drops out in conversation, stuff just drops out, and that was the stuff that I would then be shuffling back to the unit.

So successful was Simons ‘shuffling back of information’ that after a while, it was suggested that perhaps he wanted to do it “a bit more seriously”, and he left the prison system to join the military intelligence-gathering services. Ending up in the Middle East, somewhat fast-tracked, he needed operations experience under his belt, so he had to go through a selection process, “Selection is bloody arduous. It wasn’t a pleasant experience. It goes on for four months initially, but in reality, it’s probably the best part of an 8- or 9-month process.” Training across remote areas like the Brecon Beacons and Bodmin Moor, the physicality of the selection process was a lot. “Most of the guys on selection were in their late 20s or early 30s, and I think I was 48 at the time, or 49, so it was pretty painful, I can tell you that…”

"As a role, interrogation sits alongside the ‘prone to capture’ category of roles, with much of the work ‘done in the middle of nowhere', you know, or in situations where you’re way beyond help should anything happen to you. You have to be self-reliant, you have to have both the physical and the mental capabilities to put up with that, and that’s why we trained like the SAS. You have to go through that rigorous testing to weed out people who either physically will break - and it’s not about being the fastest or the quickest or anything like that because, clearly, at that age, I was neither fast nor quick - but it is that ability to keep going, especially when everything else in your body is saying to you ‘just stop’, ‘just give up’ there’s just that sheer bloody-mindedness that sheer stubbornness that says, ‘Nah, I’m going to carry on.'”

RP: Let’s go back to the idea of treating everyone as similar or building that rapport…

Simon: Like in any relationship, you establish those base layers of contact. You can build a good rapport with anyone, but there are some I got nowhere with - they were rare individuals, because everyone has that point of contact, that point of interest, or a shared view of the world, it’s always there at some level…

RP: A scale as such…

Simon: Yeah, and the thing is, coming down that scale, to those base levels of warmth, shelter and food - the three key elements of life - at some point - we all agree that we need warmth, we all need shelter, we all need food. So, you have a point on the scale to meet them at. If you agree on those three things, you can talk: how are we going to get the warmth then? How are we going to get the shelter? How are we going to get the food? You build it back up from there, and that’s an extreme example, but that’s the process.

RP: So you never start the approach with antagonism or visible distrust of that person?

Simon: I certainly wouldn’t go in to speak to someone from the Taliban and say, ‘You’re wrong, and I’m right’ because that’s my perception. Your own perception can’t come into it. That’s not the role of the work. To my mind, it’s all fairly obvious. It all stems down to how you view people, I suppose, and if you view everybody as having a justified point of view - which you might think is wrong, which I very often do, I have my viewpoint on many things - but I do realise people have viewpoints on it as well and the key element there is to find out why.

Hans Shaft:

Perhaps one of the most famous interrogators in history, aptly named ‘The Master Interrogator’, is Hans Shaft—a German Luftwaffe officer during the Second World War—known for interrogating American fighter pilots. Becoming an interrogator in 1943, he was praised for never using physical means to obtain information. Indeed, so effective were his techniques that he ended up shaping US interrogation techniques after the war, invited by the United States Air Force to lecture for them when he was granted immigration status there and even entering the military curriculum.

Simon: A lot of what we do now, a lot of my training, was based on the principles of what Hans Shaft started back in 1942, or something. In the Second World War, he looked at what a lot of what the Gestapo and the heavy-hand boys were doing and thought, “This was just nonsense” because you can’t trust the person, you know?

RP: So he tried a different approach?

Simon: Yeah, he would just chat with the people he was interrogating. He would build rapport with them in a way, not random; it all has a purpose, but it would appear random.

RP: Like, 'how’s the weather?'

Simon: Yeah! He would pass pleasantries and talk about the birds and the bees and “Isn’t the weather lovely?” and establish a point of contact with whomever he was talking to. Like they might say, “This is such and such a tree”, and he would be like, “Ah right, you’re into nature,” and he would build up a picture of that person.

RP: And get them talking…

Simon: When you get them talking, the natural instinct is to carry on talking, particularly if you’re in a very uncertain situation… Even though the person knows he isn’t really your friend, while you’re still talking, you’re still alive, right? And so once you get a person relaxed - and particularly when they start to open up about personal details - you then gently, gently, gently, gently, gently, push, push, push, and people unknowingly box themselves in. It’s no different to sales. It’s exactly what you do when you work in sales; you get a person to discuss around a thing, you know where your point is, you discuss around it and they effectively box themselves in.

Trust & Honesty:

We discussed the importance of trust within the role, particularly when building rapport, and Simon jumped back to his time in sales again: “They always say this in sales. They said it to me in training years ago, but it landed very strongly. ‘Never lie to a person’. Because if you lie and that lie is found out or suspected, you burn rapport, the rapport you’ve spent ages building up. It disappears immediately. It just burns. And despite what people say, you never, ever get it back like the first time. You’re just telling lies."

RP: So if someone was asking what was going to happen to them if they spoke to you, what would you say?

Simon: I’d say, “Honestly, I can’t tell you.”

RP: Because your part of the process was just getting them to talk?

Simon: If they ask, “Is this going to happen to me?” or “is this going to happen to me?” I’d say, “Honestly, I can’t tell you. I could tell you it’s all going to be fine and hunky dory, but that would be a lie because I don’t know.” And by approaching it that way, it’s not what they want to hear, but at least they know that what you’re telling them is true.

RP: You had to tell them a version of the truth?

Simon: When I was dealing with someone, I had to be conscious that whatever I was saying had to be the truth, or at least, to be seen to be the truth.

RP: So you could swap the truth with them?

Simon: If what I’d told them was a load of old bollocks, what they’ll tell me will be absolute bollocks too. We stop believing each other. Even when you have to tell them bad news they don’t want to hear, you’ve still told them the truth. And that fits into anything, any walk of life.

Mindset, Motivation & Expectation

For Simon, initial conversations were always about establishing the baseline and assessing who and what he was dealing with. “It comes down to MME - mindset, motivation, and expectations. Where are they in their heads? Chances are they’re really worried, they’re uncomfortable, but they have information they know they need to protect. For me, it’s figuring out what they think is going to happen.”

RP: You have to have an empathetic mind as an interrogator.

Simon: You’re genuinely trying to get a feel for that person without revealing your hand too much in that first conversation. You can assess someone in the first twenty minutes: they’re very neutral, they have their own expectations, and often, it’s just you and a pen and a bit of paper.

RP: And what are you asking them?

Simon: Simple things, like: what are you going to do about this? Why do you think you’re here? You don’t know? Okay, fantastic. Anything you want to tell me? No? Okay.

RP: You’re getting that baseline…

Simon: You’re just listening. You’re very neutral. They could go off on one, break down in tears, whatever. And I’d say, “Cry mate, when you’re ready, let’s get back to it.” At that point, it’s very much just establishing who that person is; what is that person like? Just getting that idea of them, and once you’re fairly confident that you think you have a handle on what makes them tick, what their motivation and expectation is, then you go back in and undermine all of that.

For Simon, it always begins with why the person he’s interrogating believes they’re right. What the mindset and motivation is around what they’ve done:

You have to understand the way these people think, you can’t go in there and think your opinion is right, or you have nothing. You and 99.9% of the world might know what they’re doing or have done is wrong, but you can’t go in like that because that person thinks they’re right and you have to figure out what they think they’re right.

“The intelligence you’re looking for is why they believe what they do. If you accept the fact you’re not going to change their mindset, accept the fact that in their eyes, they’re right - so don’t try to argue about it, don’t be confrontational, don’t try and change somebody - you’re just focussed on finding out 'why'. Because, at that point, all you’re trying to do is understand that mindset, and if you understand your enemy, you can counter that mindset. If you don’t understand that mindset, you’re trying to build on shifting sand. You never argue with the person you’re interrogating.”

RP: Do you think that one of the really important things in an interrogator's job is that you have to grind longer than the person in front of you?

Simon: Yeah, there is that to it, as well as long, uncomfortable silence! There is that to it, but it’s actually… you should always have a purpose. If you go into the booth, you always have to have a purpose. If you don’t have one, you shouldn’t be there; you’re wasting your and the other person’s time in the booth, in the room, and all the military’s time too.

RP: So, respectfully, you always have a purpose?

Simon: You always go with a purpose because of the mental agility it takes. If something is not working, if you’re like, where do I go from here? Then you’ve reached an impasse, and that’s when you send them back to their cell. You sit down, you have a rethink, have a reset, and then you go again.

Part Two — coming next…

Photo Credit: guo fengrui & cotton bro