The Job Killer

It’s 2019 and the presence of social media in our daily lives feels less like a tool to keep up with old friends and more like a glossy portfolio showcasing the careful balance of our professional successes paired alongside curated personality bites. Play the game right and your career has the potential to skyrocket, reaching a large audience from the comfort of your unkempt bed [just don’t Instagram it — unless, you know, that’s part of the persona your loyal followers demand]. Opt-out of this newfound hierarchy and you’re an anomaly, one who likely will receive social and professional punishment for not being a part of the system. Though the ripples of social media touch nearly every profession, artists, authors and fashion industry specialists were some of the first to see their long-term careers wane as follower count overtook.

In 2009, Facebook implemented its Likebutton, forever changing our lives with a sudden dopamine rush and a newfound awareness that our peers were engaging with what we had to say online. In 2010, Instagram rolled out its app for iPhone users only, not including Android in its repertoire until 2012 when it achieved an astounding million downloads in under one day. Before the advent of Instagram’s streamlined feed, the blogger bubble was at an all-time high, the first instance of “regular people” becoming minor internet celebrities outside of reality television.Now that blogs have been kicked by the wayside to fit into neat little boxes on these two major platforms, our Likes and Followers stand as a representation of societal credibility and, more unfortunately, our worth to the world that is advertising. As an anonymous friend and industry professional lamented, “It’s a horrible notion. Because it basically means you HAVE to feed the beast and work for Zuckerberg no matter if you like it or not. It’s a monopoly and it’s time it was broken up or regulated by the state.”

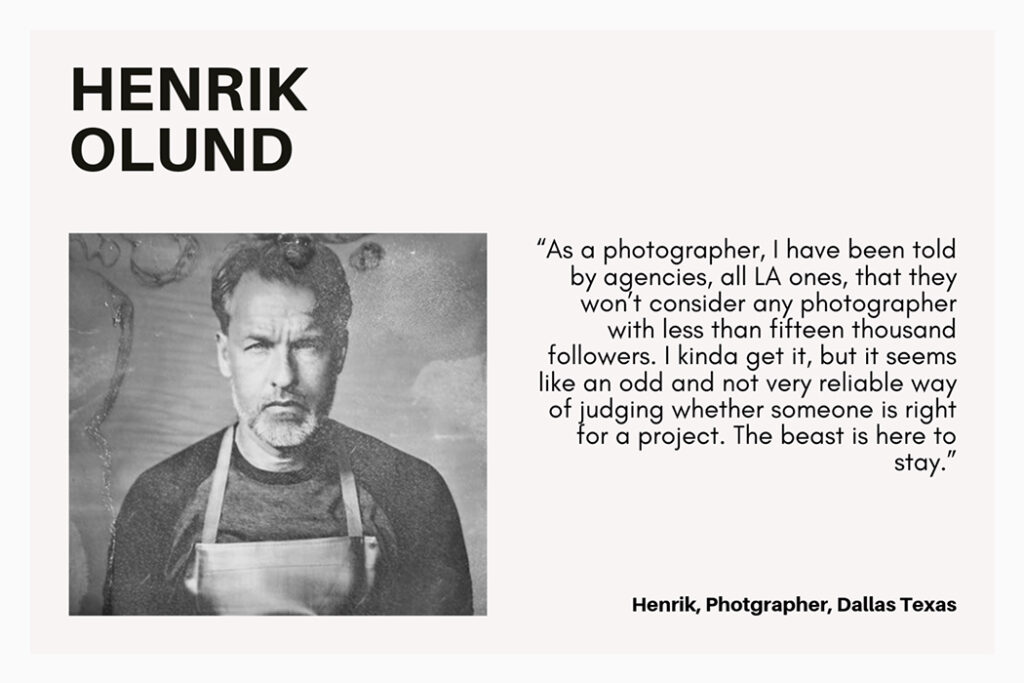

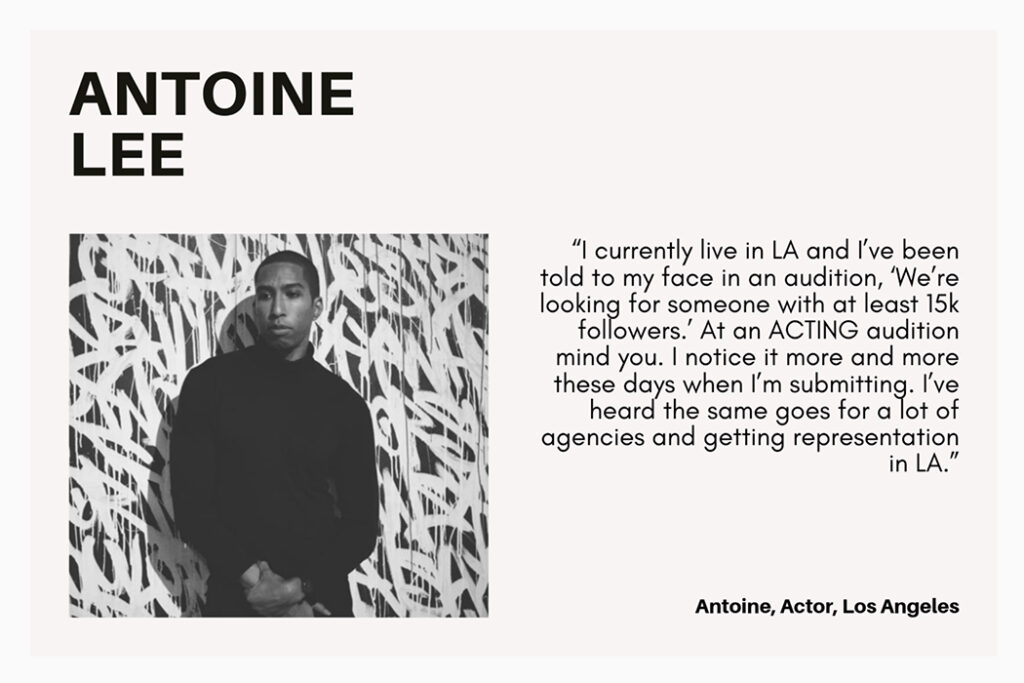

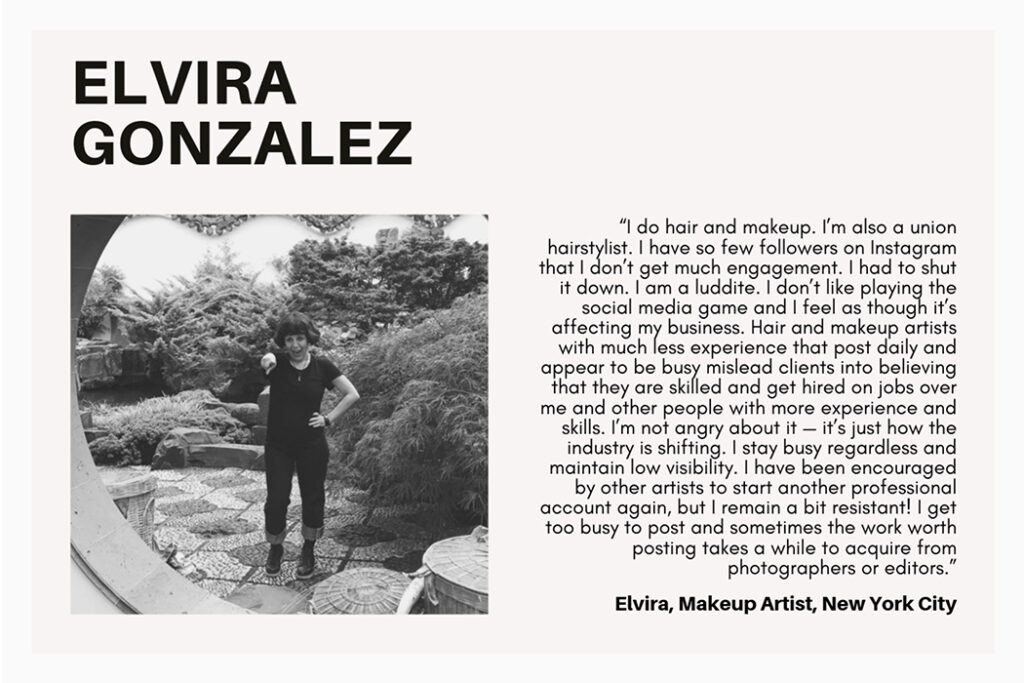

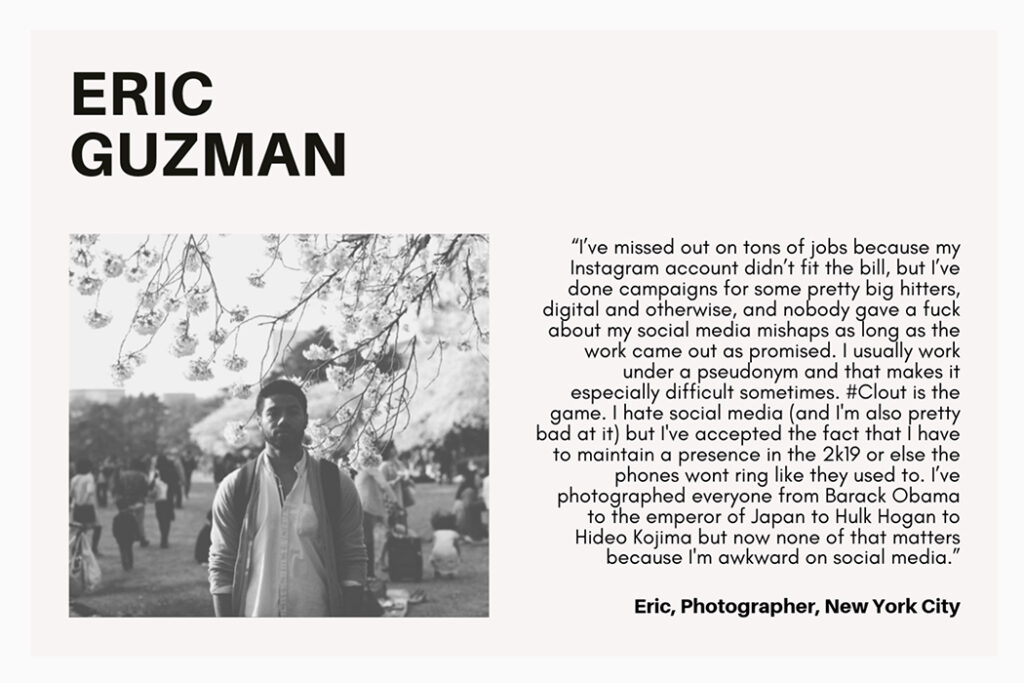

Work, particularly in fashion related fields [nepotism aside], was once based on a portfolio of gruelling professional work built up over the years. Photographers, fashion stylists, make-up artists and models alike would usually begin their careers vying for creative test shoots that might lead to broader connections and a wider portfolio range. Much like mainstream jobs, these industry creatives were usually employed based on skill level and experience. But what happens when a social media make-up artist or stylist has a recognisable face and dedicated following? As photographer Frank Nitty comments, quality is often sacrificed for quantity: "It’s definitely a trend for advertising agencies to want to work with influencers and KOLs [key opinion leaders] more than real models or even actors. I notice my peers, especially the photographers, kind of hate it. I hear them complain a lot. I can understand it from an advertising point of view because you have to compete with SO much content out there. It’s a little detrimental to the work though. People settle for less quality and more quantity. From my own experience the worst is working with KOL fashion bloggers. Compared to a professional fashion stylist, they usually just don’t know what the fuck they’re doing."

The Instagram boom has drastically altered the world of fashion; fashion week alone was once renowned as a private event, closed off to those who didn’t work exclusively in its realm. Since the advent of bloggers-turned-influencers Bryan Yambao [Bryanboy] and Rumi Neely [Fashion Toast], the streets of the function have been increasingly clogged with influencer hopefuls. However, the change in consumer habits has altogether altered the way brands release their clothing,demanding a constant influx of new items on-demand instead of the previous four-season run. It begs the question: for whom does fashion week continue? Yet many brands and events still tend to cater towards this elite-for-no-reason-crowd. Benjamin Perry Boswell, who resides in Tokyo, told us, "At quite a few fashion related events/receptions, certain PR agencies will think it’s acceptable to split up a group of friends who came togetherand put them in different areas/give them different gifts simply because some have 20k+ and some have *only* 10k+."

Recently brought to our attention by blogger Diet Prada, influencer Arielle Charnas received USD 10 million in funding to expand her “lifestyle brand”, Something Navy, at Nordstrom. Critiques have been on the influencer’s back for obvious copies of designer pieces, lack of originality and no previous experience in the design world, while others have called her out for hordes of bot comments all inexplicably repeating the same positive messages, including, “Um…ordering NOW!” With the option to purchase followers and comments at everyone’s fingertips, we arrive at a standpoint where art has turned into a numbers game, and social media strategy is often rewarded over dedication to craft.

Although it’s an easy route to discount social media and the influencer scene as a whole, there are real people behind these accounts working tirelessly to maintain their image. Social media management rightfully became a full-time position at the advent of the success of these major social platforms. It’s a job in itself, and for hopefuls on the rise it’s often an unpaid one, a goal that leaves many in debt, or a realm that is inaccessible to all demographics who don’t fit into the white and privileged archetype. In true democratic fashion, we are in control of who rises to the top, we vote with our likes, and our collective obsession with Kardashian-esque styles and curated profiles are the reason we got here in the first place. The real quandary is, how do those who built their careers on real world experience with no interest in social media fit into this experiment? Insider knowledge points to a shift in the system, as brands are dropping 20 to 100k per post and seeing unmatched output and younger people are not as interested in social media as their older peers. At what seems like the extreme end of our social experiment, the pendulum is in motion for a reverse swing. We hope the future holds a balance that with save all of our sanities.

What does this mean for brands? As younger audiences remain hyper vigilant about sponsored content, the age of investing in an influencer simply due to numbers may be coming to a close. As Ruby commented in her Seeding article, researching unique creatives with interesting and strong stories to tell is the modern approach to expanding brand power worldwide.